Second Chapter: The Northern Correspondent

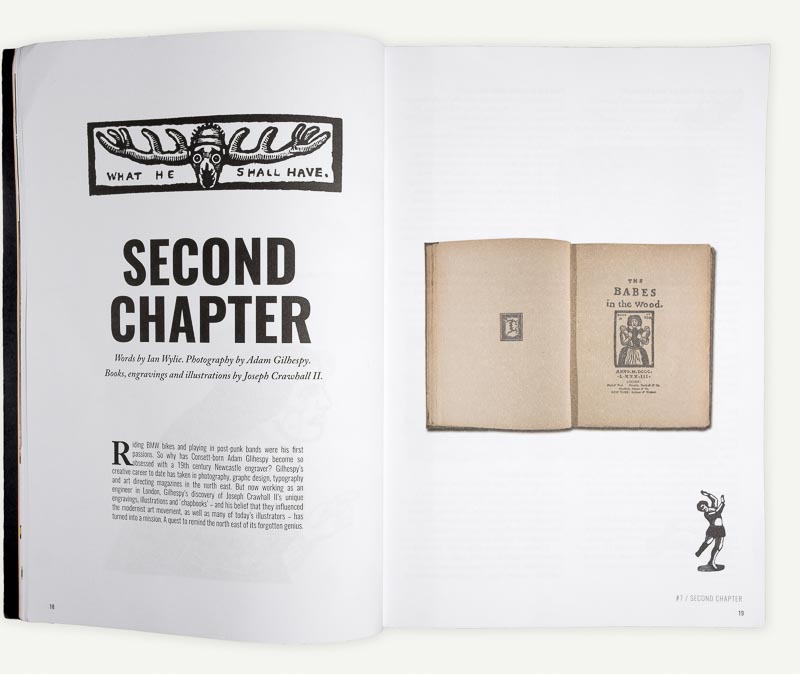

Northern Correspondent editor Ian Wylie interviewed me about my Joseph Crawhall II project for issue #7 (Lost & Found, March 2016). Designer Michelle Pegg got carried away and used JCII reproductions throughout the issue

Riding BMX bikes and playing in post-punk bands were his first passions. So why has Consett-born Adam Gilhespy become so obsessed with a 19th century Newcastle engraver? Gilhespy’s creative career to date has taken in photography, graphic design, typography and art directing magazines in the north east. But now working as an engineer in London, Gilhespy’s discovery of Joseph Crawhall II’s unique engravings, illustrations and chapbooks—and his belief that they influenced the modernist art movement as well as many of today’s illustrators—has turned into a mission to remind the north east of its forgotten genius.

How did you first find out about Crawhall?

I have a friend, Deirdre Thompson, who knows her history of north east art, especially book printing and binding. And yet she’d never heard of Crawhall until she discovered him at the Lit and Phil, where Crawhall had donated a copy of each of his books. 'You’ve got to see this!' she said, and it was the start of a journey for both of us, as we realised just how good this guy was, how influential he was in certain circles, his importance to English modernism. So I created a website about him, bought a rostrum, lighting stand and all the gear to do hardcore photography of Crawhall’s books that I’d bought, begged or borrowed. And I’ve been converting people along the way. I found some stuff in the Keel Row Bookshop in North Shields and asked the dealer Anthony Smithson there to keep an eye out for more. He’s become such a fan himself that his website and even his van now carry Crawhall illustrations.

What do we know about Crawhall?

Crawhall was a wood engraver. Newcastle has a long tradition of wood engraving, stretching even beyond Thomas Bewick, the master. Crawhall’s engraving style was very different from Bewick’s, but he was the executor of Bewick’s daughter’s will when she died, so they all knew each other. He was born into a Newcastle mercantile family. Crawhall’s father, Joseph Crawhall I, had a big ropemaking business on St Anne’s Quay–the road down the Newcastle’s Quayside from where the old Star and Shadow cinema used to be is called Crawhall Road. He was also mayor and sheriff of Newcastle. But Joseph Crawhall I was also an artist himself. I’ve seen one of his pencil and watercolours in the National Portrait Gallery in London, so he was a pretty competent amateur. When he designed a chimney for his factory, he shaped it like a coiled rope–an example of the artist as engineer.

He passed this love of art on to this son, who in turn passed it on to his son, Joseph Crawhall III, who became a notable water colourist associated with the Glasgow Boys. The continued success of the family business generated the wealth that allowed them to explore their creative pursuits. Aside from being an engraver, Joseph Crawhall II made books and that’s where I get interested. His engravings are thrilling, but as whole objects the books are absolutely beautiful. He was deeply engaged with the entire process of making books, and was as interested in the design and words as he was in the illustrations.

What was so special about his books?

He published his first couple of books locally through Newcastle printer Mawson, Swan and Morgan. It’s said that every book he ever made turned a profit, but those first books were quite rough. Later he met another publisher, Andrew Tuer who ran the Leadenhall Press in London, who shared his interests in the revival of chapbooks. Started in late medieval times, these were rough-printed pamphlets sold to the relatively poor. Back then, books were hardbacks chained to library shelves, elite things to own. In contrast, chapbooks contained folk tales and hymns, things that appealed to a less educated audience. Newcastle had been a relatively important player in the making of chapbooks, and Crawhall, who was interested in antiquity and campaigned to preserve the city’s medieval architecture, was reviving the tradition.

Was Crawhall an artist who was aware of his influence?

I don’t think Crawhall saw himself on the cutting edge of modernism. He just got a kick out of it, making quaint and funny little books that harked back to an era that he enjoyed. But I suppose it wasn’t dissimilar to what modernists such as Picasso did, looking back for inspiration to old African sculptures and Japanese prints. There was an appeal to the rough and primitive, as a reaction to the dulling of renaissance artwork. Crawhall was a part of this movement, but not entirely aware of it.

Some of the spreads in his books are really radical–there’s lots of white space and typography stuff that became hallmarks of modernism in book design. Tuer and Crawhall had a typeface designed and cut from for these books which was no small undertaking. While the Mawson Swan and Morgan books were essentially rough paperbacks, the Crawhall books published by Tuer are gorgeous hardbacked, leather-bound creations.

What are your favourites?

I love Izaak Walton's Wallet Booke. Walton had written The Compleat Angler, the bible of fishing. Crawhall wrote a book as if it were Walton’s notebook, but completely taking the piss. Bound into the book is a wallet for your fishing flies and another for your tobacco. But what’s so stunning is the quality of illustration that he puts alongside this sense of humour. Humour ran through all his books. He decided to remake Chorographia, which is quite a serious survey of Newcastle. But he still manages to sneak in jokes and funny pictures. There is a gorgeous goat-skinned copy of Chorographia in the Lit and Phil which is probably the nicest book I’ve ever had in my hands. Even some of his early stuff for Mawson, Swan and Morgan is completely beautiful, such as his ABC for children.

After Crawhall, it become a tradition in English art to do an ABC book for children. It was called Old Aunt Elspa’s ABC–it was Crawhall’s nickname for his daughter–and you find out that, for example, R is for racket, rumpus and riot, accompanied by an illustration of Crawhall being beaten by his wife. It’s the earliest example I know of a serious artist doing a children’s ABC book, and since then it’s a project that’s been repeated by everyone from Peter Blake to the Beggarstaff Brothers who were pivotal to the development of English commercial art.

How did he influence the Beggarstaffs?

Little of the Beggarstaffs' work has survived because much of it was commercial posters for theatre productions, pasted to walls, then torn down or pasted over. One of their posters, for a production of Hamlet, is in New York’s MoMA museum, so they are regarded as pretty important. And if you look at that Hamlet poster and see how reductive it is, reducing imagery to its bare essentials - then you can begin to detect the influence of Crawhall on modernism. Another artist influenced by Crawhall, particularly his use of asymmetry, was Edward Gordon Craig who influenced German expressionism through work he did with private presses in Weimar.

Why has the importance of Crawhall been lost?

He hasn’t been lost entirely–the top floor of the old Central Library in Newcastle used to display a letter, sketch, pipe and book by Crawhall in a glass vitrine. But in the public mind he has been completely forgotten. I wonder if the reason is partly political. High Victorians like Crawhall became unpopular in Newcastle as the political mood of the city moved to the left. But another reason may be that he wasn’t a painter, but someone who made little books which weren’t so readily displayed in art galleries and instead disappeared into the shelves of the Lit and Phil.

There is one biography of Crawhall, and by all accounts he seems to have been an adorable guy with a good sense of humour, who lived a happy life with his wife and children. He was occasionally ill which sent him into bouts of melancholy. And he also seemed to have slight obsession with medieval torture equipment. But there are no salacious stories about him. I see Crawhall influences all the time in the work of today’s illustrators, such as the illustrations from the east London “I went to art school but they didn’t teach me how to draw” movement. And when I show illustrators Crawhall’s work, they go mad about it. So it seems important to bring him to people’s attention.

Why does Crawhall resonate so much with you?

I grew up in Newcastle in the early Noughties when the city had a DIY, post-punk, neo primitive element to it–and that chimes with Crawhall–a guy in the 19th century who was a punk avant-la-lettre. I would love to see a major Crawhall exhibition at the Laing Art Gallery and I’m going to try to make that happen.